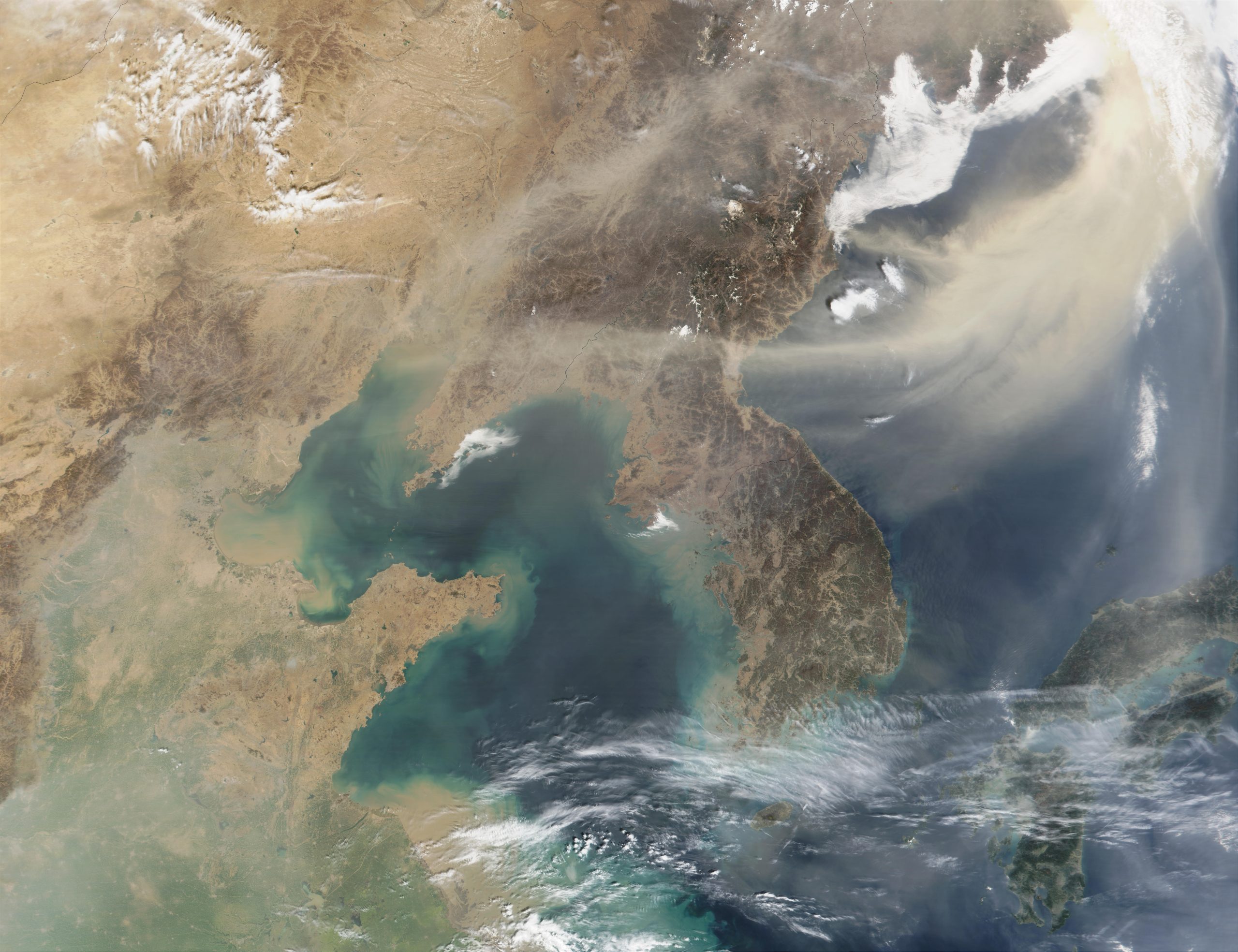

Révéler le rôle caché de la poussière – nourrir les océans et réguler le changement climatique

Poussière de Chine. Crédit : Observatoire de la Terre de la NASA

Un scientifique de l’Oregon State University mène de nouvelles recherches qui visent à découvrir le rôle de la poussière dans le maintien des écosystèmes océaniques mondiaux et le contrôle des niveaux de dioxyde de carbone dans l’atmosphère.

Les chercheurs ont depuis longtemps reconnu que le phytoplancton, les organismes ressemblant à des plantes qui vivent dans la couche supérieure de l’océan et servent de base à la chaîne alimentaire marine, dépendent de la poussière de sources terrestres comme nutriments essentiels. Cependant, la quantification de l’étendue et de l’ampleur de l’impact de cette poussière – des particules provenant de sources telles que le sol qui sont transportées par les vents et affectent le climat de la Terre – s’est avérée difficile.

« C’est vraiment la première fois, en utilisant les enregistrements d’observation récents et à l’échelle mondiale, que les nutriments transportés par la poussière qui s’accumule dans l’océan créent une réponse dans la biologie de la surface de l’océan », a déclaré Toby Westbury. Océanographe de l’Oregon et auteur principal de l’article qui vient d’être publié dans les sciences.

L’océan joue un rôle important dans le cycle du carbone ; Le dioxyde de carbone de l’atmosphère se dissout dans les eaux de surface, car le phytoplancton convertit le carbone en matière organique à travers lui[{ » attribute= » »>photosynthesis. Some of the newly formed organic matter sinks from the surface ocean to the deep sea, where it is locked away, a pathway known as the biological pump.

In the new paper, Westberry and other scientists from Oregon State; the University of Maryland, Baltimore County; and NASA Goddard Space Flight Center estimate deposition of dust supports 4.5% of the global annual export production, or sink, of carbon. Regional variation in this contribution can be much higher, approaching 20% to 40%, they found.

Australia dust. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

“That’s important because it’s a pathway to get carbon out of the atmosphere and down into the deep ocean,” Westberry said. “The biological pump is one of the key controls on atmospheric carbon dioxide, which is a dominant factor driving global warming and climate change.”

In the ocean, vital nutrients for phytoplankton growth are largely provided through the physical movement of those nutrients from deep waters up to the surface, a process known as mixing or upwelling. But some nutrients are also provided through atmospheric dust.

To date, the understanding of the response by natural marine ecosystems to atmospheric inputs has been limited to singularly large events, such as wildfires, volcanic eruptions, and extreme dust storms. In fact, previous research by Westberry and others examined ecosystem responses following the 2008 eruption on Kasatochi Island in southwestern Alaska.

In the new paper, Westberry and Michael Behrenfeld, an Oregon State professor in the Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, along with scientists from UMBC and NASA built on this past research to look at phytoplankton response worldwide.

Westberry and Behrenfeld focused their efforts on using satellite data to examine changes in ocean color following dust inputs. Ocean color imagery is collected across the global ocean every day and reports changes in the abundance of phytoplankton and their overall health. For example, greener water generally corresponds to abundant and healthy phytoplankton populations, while bluer waters represent regions where phytoplankton are scarce and often undernourished.

Australia dust. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

The scientists at UMBC and NASA focused their efforts on modeling dust transport and deposition to the ocean surface.

“Determining how much dust is deposited into the ocean is hard because much of the deposition occurs during rainstorms when satellites cannot see the dust. That is why we turned to a model,” said UMBC’s Lorraine Remer, research professor at the Goddard Earth Sciences Technology and Research Center II, a consortium led by UMBC. The UMBC team used observations to confirm a NASA global model before incorporating its results into the study.

Working together, the research team found that the response of phytoplankton to dust deposition varies based on location.

In low-latitude ocean regions, the signature of dust input is predominately seen as an improvement in phytoplankton health, but not abundance. In contrast, phytoplankton in higher-latitude waters often show improved health and increased abundance when dust is provided. This contrast reflects differing relationships between phytoplankton and the animals that eat them.

Lower latitude environments tend to be more stable, leading to a tight balance between phytoplankton growth and predation. Thus, when dust improves phytoplankton health, or growth rate, this new production is rapidly consumed and almost immediately transferred up the food chain.

At higher latitudes, the link between phytoplankton and their predators is weaker because of constantly changing environmental conditions. Accordingly, when dust stimulates phytoplankton growth, the predators are a step behind, and the phytoplankton populations exhibit both improved health and increased abundance.

The research team is continuing this research, bringing in improved modeling tools and preparing for more advanced satellite data from NASA’s upcoming Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem (PACE) satellite mission, some of which will be collected by the UMBC-designed and -built HARP2 instrument.

“The current analysis demonstrates measurable ocean biological responses to an enormous dynamic range in atmospheric inputs,” Westberry said. “We anticipate that, as the planet continues to warm, this link between the atmosphere and oceans will change.”

Reference: “Atmospheric nourishment of global ocean ecosystems” by T. K. Westberry, M. J. Behrenfeld, Y. R. Shi, H. Yu, L. A. Remer and H. Bian, 4 May 2023, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.abq5252