Nouvelle ère de recherche sur la supraconductivité – Des scientifiques découvrent la matière des « boucles d’or »

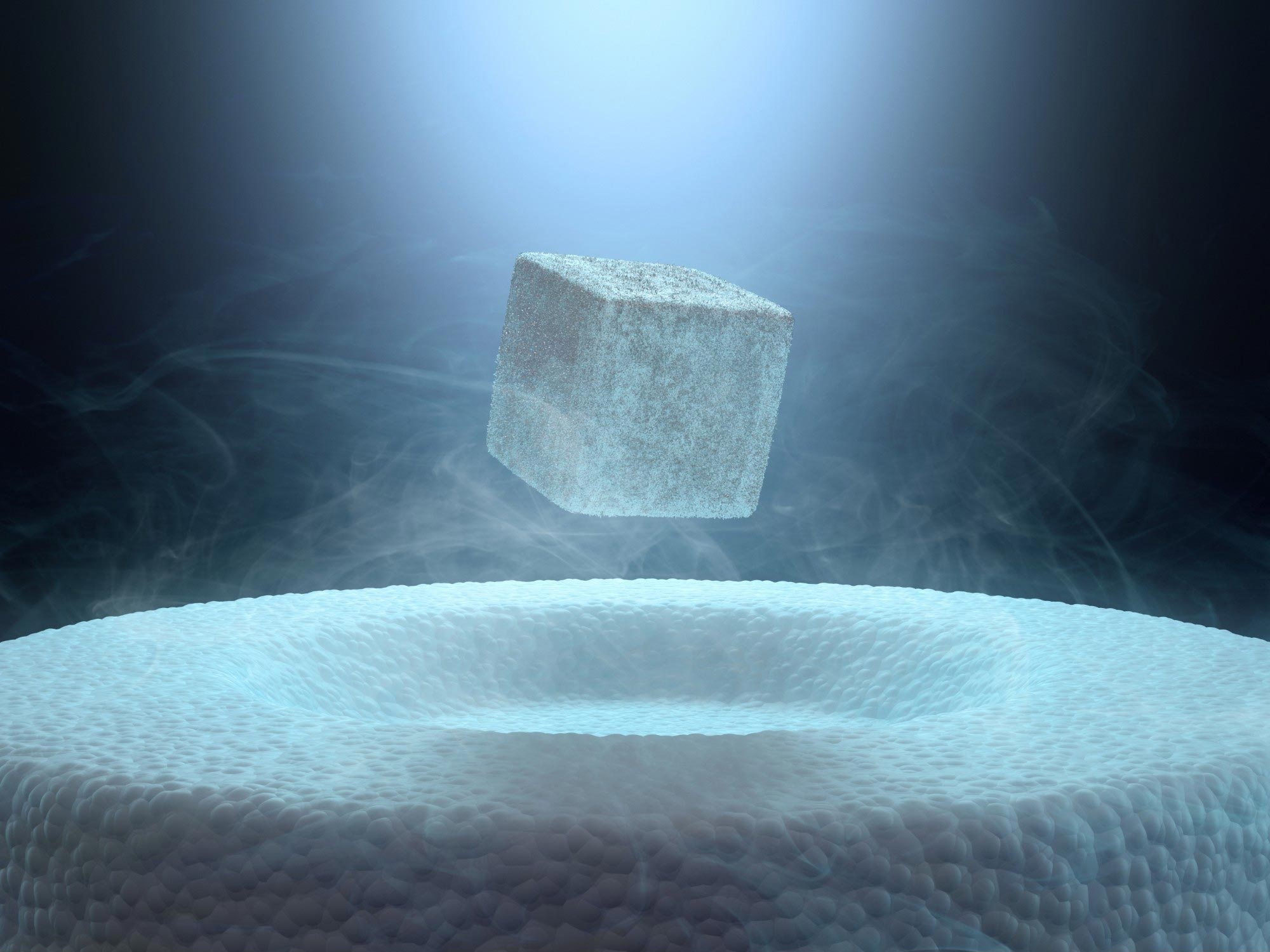

Des chercheurs de TU Wien et d’universités japonaises ont utilisé des simulations informatiques pour déterminer la « région dorée » pour une supraconductivité optimale. Cette région, où l’interaction entre les électrons est forte mais pas trop forte, est atteinte avec une nouvelle classe de matériaux appelés palladates, qui pourrait inaugurer une nouvelle ère de recherche sur la supraconductivité.

TU Wien a effectué des calculs qui suggèrent d’utiliser le métal précieux palladium comme « Goldilocks » pour créer des supraconducteurs qui restent supraconducteurs même à des températures relativement élevées.

Dans le domaine de la physique moderne, une entreprise exaltante est en cours : déterminer la méthode optimale pour créer des supraconducteurs qui maintiennent la supraconductivité à des températures et pressions ambiantes élevées. Cette entreprise a été revitalisée ces derniers temps par l’avènement du nickel, inaugurant une nouvelle ère de supraconductivité.

La base de ces supraconducteurs réside dans le nickel, ce qui a conduit de nombreux scientifiques à qualifier cette période de recherche sur la supraconductivité de « l’âge du nickel ». À bien des égards, les nickels sont similaires aux cuivres, qui ont été trouvés dans les années 1980 et sont à base de cuivre.

Mais maintenant, une nouvelle classe de matériaux entre en jeu : en collaboration entre TU Wien et des universités japonaises, il a été possible de simuler le comportement de différents matériaux sur un ordinateur avec plus de précision qu’auparavant.

Il y a une « Goldilocks Zone » dans laquelle la supraconductivité fonctionne bien. Et cette région n’est pas atteinte avec le nickel, ni avec le cuivre, mais avec le palladium. Cela pourrait inaugurer une « nouvelle ère des appartements » dans la recherche sur la supraconductivité. Les résultats viennent d’être publiés dans la revue scientifique

The search for higher transition temperatures

At high temperatures, superconductors behave very similarly to other conducting materials. But when they are cooled below a certain “critical temperature”, they change dramatically: their electrical resistance disappears completely and suddenly they can conduct electricity without any loss. This limit, at which a material changes between a superconducting and a normally conducting state, is called the “critical temperature”.

“We have now been able to calculate this “critical temperature” for a whole range of materials. With our modeling on high-performance computers, we were able to predict the phase diagram of nickelate superconductivity with a high degree of accuracy, as the experiments then showed later,” says Prof. Karsten Held from the Institute of Solid State Physics at TU Wien.

Many materials become superconducting only just above absolute zero (-273.15°C), while others retain their superconducting properties even at much higher temperatures. A superconductor that still remains superconducting at normal room temperature and normal atmospheric pressure would fundamentally revolutionize the way we generate, transport, and use electricity. However, such a material has not yet been discovered.

Nevertheless, high-temperature superconductors, including those from the cuprate class, play an important role in technology – for example, in the transmission of large currents or in the production of extremely strong magnetic fields.

Copper? Nickel? Or Palladium?

The search for the best possible superconducting materials is difficult: there are many different chemical elements that come into question. You can put them together in different structures, you can add tiny traces of other elements to optimize superconductivity. “To find suitable candidates, you have to understand on a quantum-physical level how the electrons interact with each other in the material,” says Prof. Karsten Held.

This showed that there is an optimum for the interaction strength of the electrons. The interaction must be strong, but also not too strong. There is a “golden zone” in between that makes it possible to achieve the highest transition temperatures.

Palladates as the optimal solution

This golden zone of medium interaction can be reached neither with cuprates nor with nickelates – but one can hit the bull’s eye with a new type of material: so-called palladates. “Palladium is directly one line below nickel in the periodic table. The properties are similar, but the electrons there are on average somewhat further away from the atomic nucleus and each other, so the electronic interaction is weaker,” says Karsten Held.

The model calculations show how to achieve optimal transition temperatures for palladium data. “The computational results are very promising,” says Karsten Held. “We hope that we can now use them to initiate experimental research. If we have a whole new, additional class of materials available with palladates to better understand superconductivity and to create even better superconductors, this could bring the entire research field forward.”

Reference: “Optimizing Superconductivity: From Cuprates via Nickelates to Palladates” by Motoharu Kitatani, Liang Si, Paul Worm, Jan M. Tomczak, Ryotaro Arita and Karsten Held, 20 April 2023, Physical Review Letters.

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.130.166002